Directed by Paul Schrader. Written by Leonard Schrader and Paul Schrader

In Paul Schrader’s debut feature Blue Collar, there’s a massive billboard towering over Detroit that keeps a live count of the number of cars built on the Ford assembly line for that given year. Its number is in the millions, but upwards it steadily ticks. A tidy, sanitized figure erected in bright lights, climbing like a sports score.

That number belies the filthy machine that puts all these cars together. Long before these assembly lines were automated and clean, they were oil- and sweat-stained heaving chains pulled by manpower; thousands of workers producing a near endless supply of cars through sheer collective exertion. This jungle of creation is referred to simply as “the line” in Blue Collar and it must always keep moving.

In Blue Collar, Schrader shows us how the line keeps moving at the cost to those who move it. It’s grueling work, crooked unions, and a rigged system guarding the status quo with brazen force. Schrader directs with the energy to match, and with this debut, he shows exactly what kind of filmmaker he’d go on to be for another four decades (and counting!) directing with guts that are afire with indignant anger. Working class oppression is detailed with a heavy hand that seems proportional to the frustration felt.

There’s a sense of authenticity first and foremost, with Schrader not sparing us any gritty detail. It’s all toil in this metal sweatshop where a weeny of a middle manager is either telling you to work faster or get back on the line. Outside’s where the real pain is. For family men, it’s bills, the tax man hovering, and the fear of not being able to provide for your family. For others, it’s drinking until you’re nodding off with eight empties in front of you in a dive bar. All wake up the next day and do it again. It’s the line, never stopping, unending.

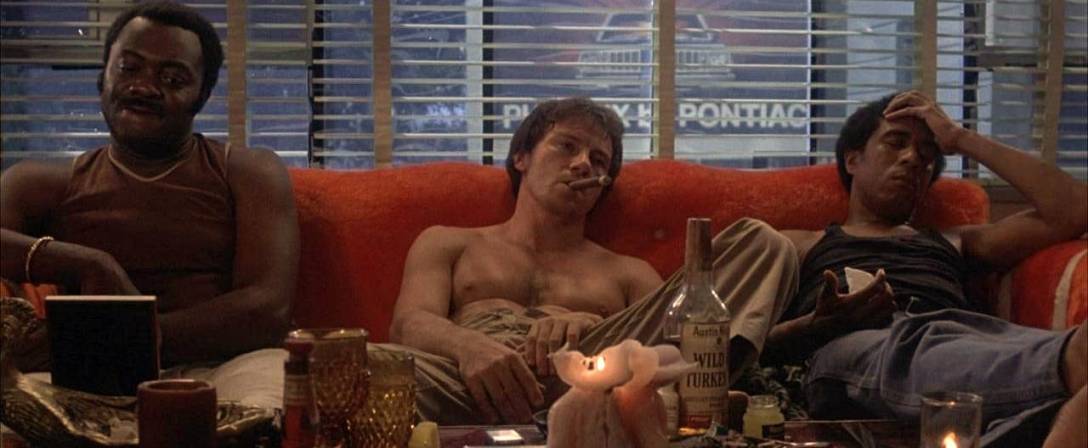

On the line are workers Zeke, Jerry and Smokey, played by Richard Pryor, Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto. Zeke’s a shit-stirring fast-talker more frustrated than the rest with the powers that be. Jerry, a White man, coasts a bit more on a belief that better days are ahead for him with little to back it up. A small example of White privilege, even in working class circumstances. Smokey, who’s got a prison stint behind him, makes no bones about the system, and has no fucks left to give.

Opportunity arises for them to knock over the lap dog union they’re part of, but in the vault they find something far more valuable than money, and once in possession of something truly damaging to the higher-ups, the three men realize the full extent of how far the powerful will go to keep them shut up.

Blue Collar has a point-of-view and its rough edges in communicating it, but it’s not a diatribe. Schrader does love the sinner, even if he hates the sin, and he takes plenty of time to show us these men as people first, and workers second. Whatever happens to Zeke, Jerry, and Smokey, we know them with all their flaws, but that doesn’t detract from the essentially good people they are, living normal lives and not asking for much.

Pryor, Keitel and Kotto have genuine chemistry and their interplay gleams amongst the grime. The way they bounce off each other with such lived-in camaraderie also makes you think Blue Collar is a goofy buddy comedy that only pretends at its serious subject matter. That’s later dispelled though, and the mood keeps curdling until Schrader throws the whole rotten affair at the screen, showing us with poorly concealed anger how everyone is brought low by the state of affairs.

Blue Collar is fueled by anger, but it has an affection for its characters that is essential. Zeke, Jerry and Smokey are not God’s children, but Schrader’s insistent they still deserve better than what they get. Schrader’s filmography is one marked by misanthropy and a crestfallen view of the world, but in this story of three men getting ground down in capitalism’s gears, there’s still a human heart at play, exactly because there is an anger to it. Schrader hadn’t given up despite his grievances, and he still hasn’t, all these years later.

With Zeke, Jerry and Smokey, he places human concerns front and center, and it makes the undoing of them all the more devastating. Why? Because these men, and all of us by extension, will be set upon by companies, either as workers or consumers, in service of some arbitrary KPI, flat and inhumane, but worshiped above everything else. That number must keep climbing, and the cars must keep coming, even when there’s no one left to drive them.