Directed by Tsai Ming-liang. Written by Yi-chun Tsai, Pi-ying Yang, and Tsai Ming-liang

It sounds quaint now, but before social media alienated us from each other, it was urbanization and its material emphasis that had us weeping in the shower. A modernizing world full of foreign imports, foreign fashion, a foreign way to be, convinced us of its necessity, then barred it from us behind a prohibitive price point despite being advertised everywhere one was able to turn your head.

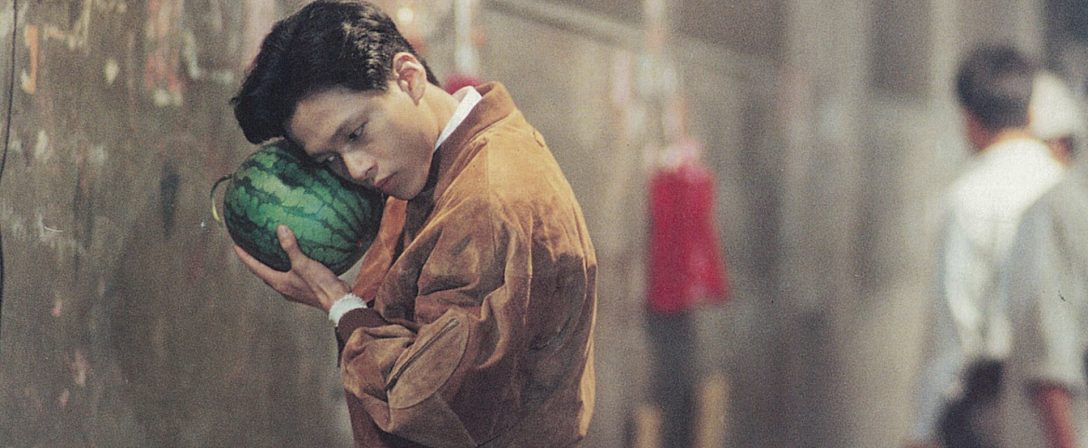

That urban alienation is the crux of Vive L’amour, Tsai Ming-liang’s second film, and it’s an expansion of his preoccupations in Rebels of the Neon God, the story of teens and 20-somethings drowning in big city life’s ennui. Here, a depressed cremation urn salesman (Kang-sheng Lee), a street peddler (Chen Chao-jung) and a struggling realtor (Kuei-Mei Yang) all use the same upscale apartment as a flop house of sorts, only they’re unaware they’re cohabitating.

Who can blame them? The apartment is more of a show model in an likely empty high rise full of these marbled display cases of newfound wealth; it holds some sparse furniture, no bedding, and there’s enough space for movement to echo around the walls. It is a haunted house by all means. The three move in silence so as to not draw attention to themselves, reducing themselves to mere ghosts. Will that change?

Three young professionals hanging on to their lives by a thread all squatting in an empty apartment that’s way beyond their means is a heavy-handed metaphor for a lost generation bedeviled by a capitalist system, but that’s the thrust of Vive L’amour, which shrouds itself in this existential malaise and whimpers its point from somewhere in the dismal fog.

It’s concept over character, and while there’s no mistaking Ming-liang’s intentions, a fact underlining his ability to evoke these nebulous feelings that can be so hard to put a finger on, let alone communicate, he does struggle to give true life to his cast of characters. As if a spoken word would break the trance, Ming-liang favors quiet observation and there’s a lot of noodling around by our central cast.

There are a few arresting moments, marked by their boldness, their surprising levity, their tenderness, but these all feel like the bones around which Ming-liang wants to build his film around but doesn’t quite manage. In the style of the slow cinema that will come to define him, he teases and toes closer to these adrift souls, but he doesn’t close the distance, leaving them cautionary tales, but not real characters.

There’s no denying the fire that burns in Ming-liang’s guts and how it puts into sharp relief a social ill. There’s also no denying the tenderness with which Ming-liang can embrace his characters, offering a soft look at those on the margins without sanctifying them. What’s missing in Vive l’amour is perhaps some rigor and what there’s too much of is perhaps some reticence. The effect, in this moody but catch-you-off-your-guard funny story about youth lost in society’s rotten sauce, is an uneven inelegance, like a dog circling itself a few times before finally coming to rest.

It’s perhaps ironic that Ming-liang would release his masterpiece Goodbye, Dragon Inn nine years later, and it would be such a wonder because he doubles down on his narrative minimalism to a point where everything became a universal stand-in, but Vive l’amour, despite being proof that Ming-liang is the real deal, doesn’t transcend the same way, ending up limited instead.